Meet butyrylcholinesterase!

Better known as BChE, butyrylcholinesterase was recently identified as a possible indicator of SIDS risk (scientists are not sure about this quite yet).

SIDS (sudden infant death syndrome) can occur in a vulnerable infant during a critical developmental period when they experience an outside stressor.* A lot of research efforts have been invested in identifying stressors and the resulting safe sleep recommendations–such as placing infants on their backs to sleep–have significantly decreased the incidence of SIDS in the U.S. over the past decade.** The timing of SIDS deaths easily reveals the critical period. Now, the active question in SIDS research remains: What makes an infant vulnerable?

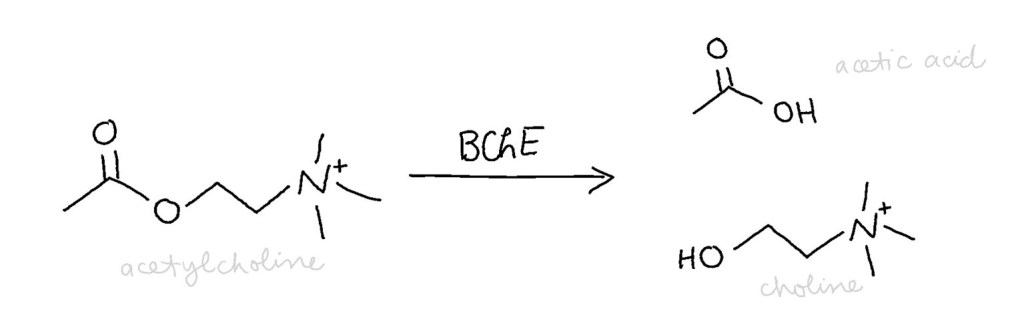

Like many proteins, BChE is named for its job: cutting up the neurotransmitter acetylcholine (Ach). Ach, and by extension, BChE, plays a role in controlling involuntary processes within the body such as sleep. More BChE means less Ach.

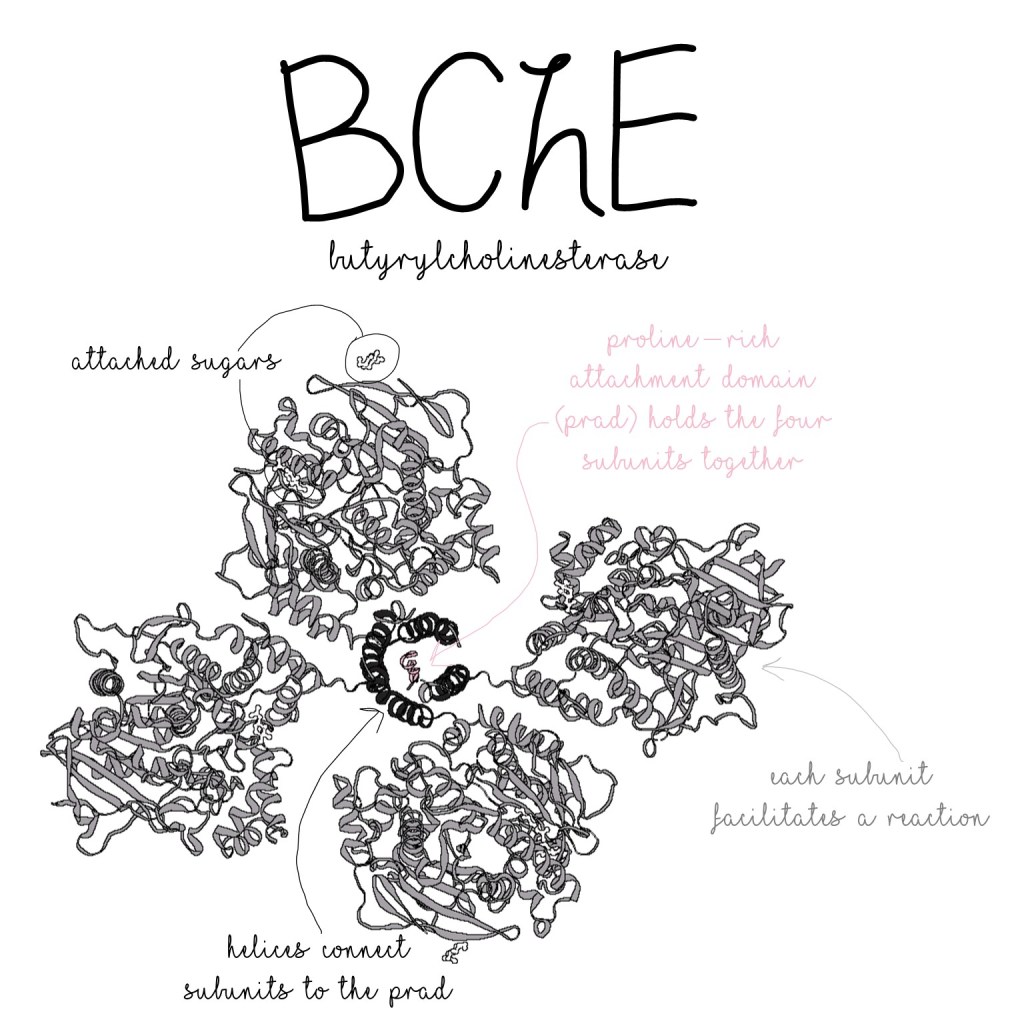

In the bloodstream, BChE units gather and work as groups of four. Each unit has a helix on one end (indicated in black below). These helices twist around another small peptide called a proline-rich attachment domain or PRAD (pink) which holds them together. The larger, blobby parts of the BChE units are where the cutting reaction takes place (grey) and these also protect the superhelix around the PRAD.

Though BChE is named for cutting Ach, it isn’t incredibly specific. It can also cut up several other molecules with similar bonds. BChE is often used as a treatment for poisoning by things like organophosphorus pesticides or even cocaine.

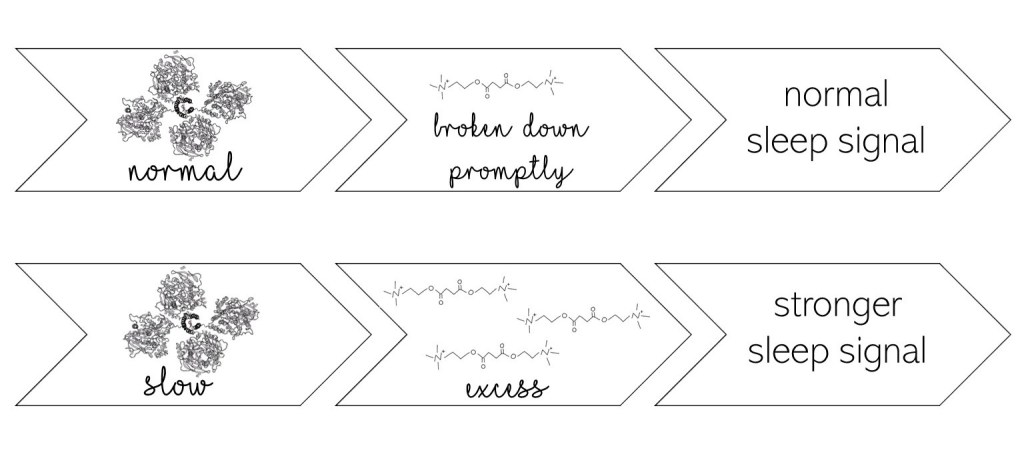

BChE also cuts up succinylcholine, a muscle relaxant used for anesthesia during surgeries. When a patient’s body fails to clear out the succinylcholine, they can go into a dangerous state of apnoea. Later research found that “patients who experienced prolonged apnoea had unusual variants of BChE with reduced catalytic activity” (Darvesh et al, 2003). In other words, if a person had poorly functioning BChE, it was harder for them to get rid of signals to sleep.

A trio of female scientists recently published their findings that lower amounts of BChE correlated with SIDS deaths.*** (They didn’t find any correlation with non-SIDS infant deaths.) This is the current hypothesis:

Reduced BChE activity makes it harder to wake up from sleep, so when the outside stressor is present, the baby does not wake in response and death results.

As enthusiastic as parents everywhere may get, remember that this is JUST A HYPOTHESIS! This study does not explain the cause of SIDS. There’s lots of work to be done before we can confidently understand the cause.

In the meantime, this study does provide a stepping stone towards mitigating SIDS risk. Perhaps adding BChE checks to the standard newborn blood screenings could save lives, just like PAH checks do (read about PAH here!). However, it is critical that researchers, doctors, and policy-makers confidently understand indicators of vulnerability before screenings are added and recommendations are changed. Implementing BChE screenings too soon could encourage parents of children that test “normal” for BChE activity to assume they are in the clear and stop appropriate precautions prematurely.

BChE is a key protein in many biological functions, and researching it in the context of SIDS shows great promise for saving babies and their families in the future.

*Filiano J, J, Kinney H, C, 1994, Neonatology, doi: 10.1159/000244052

**https://www.sids.org/what-is-sidssuid/incidence/

***Harrington, Hafid, and Waters, May 2022, the Lancet, doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104041

Lockridge, 2014 review, Pharmacology & Therapeutics

Structure: Leung et al, 2018, PNAS (PDB: 6I2T)