As part of their check-up at birth, babies get a prick on the heel. Among many other things, the blood tests for the function of a protein called phenylalanine hydroxylase. (Scientists sometimes call it “PAH” for convenience.)

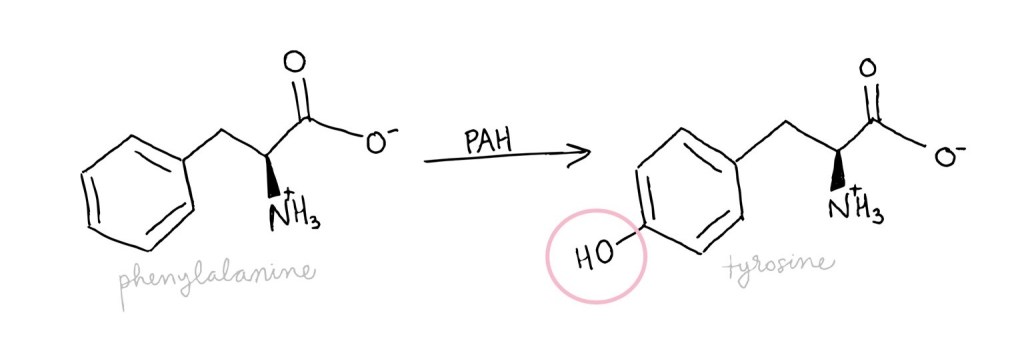

PAH is the first in a sequence of enzymes that break down excess phenylalanine. It speeds up the reaction that changes phenylalanine into tyrosine, and the rate of this first reaction sets the pace for all the others following after.

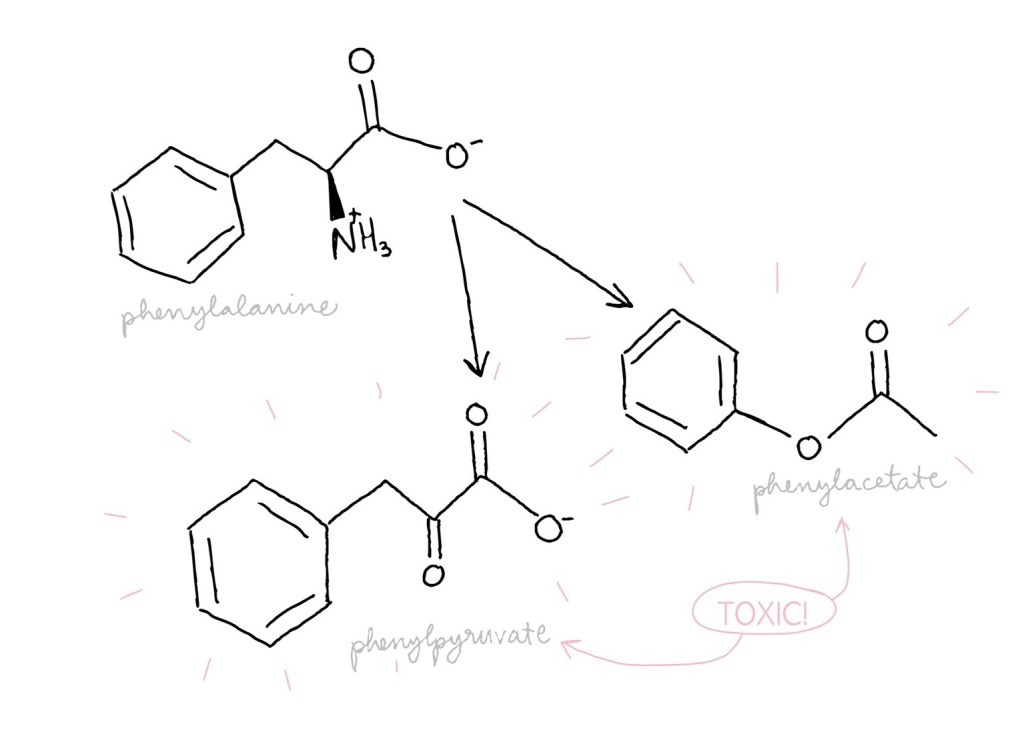

Phenylalanine, an amino acid, is used to build other proteins. Unused phenylalanine, though, can be converted into other molecules such as phenylacetate and phenylpyruvate which are toxic. It is critical that PAH is working well to avoid too much phenylalanine, and thus toxins, building up.

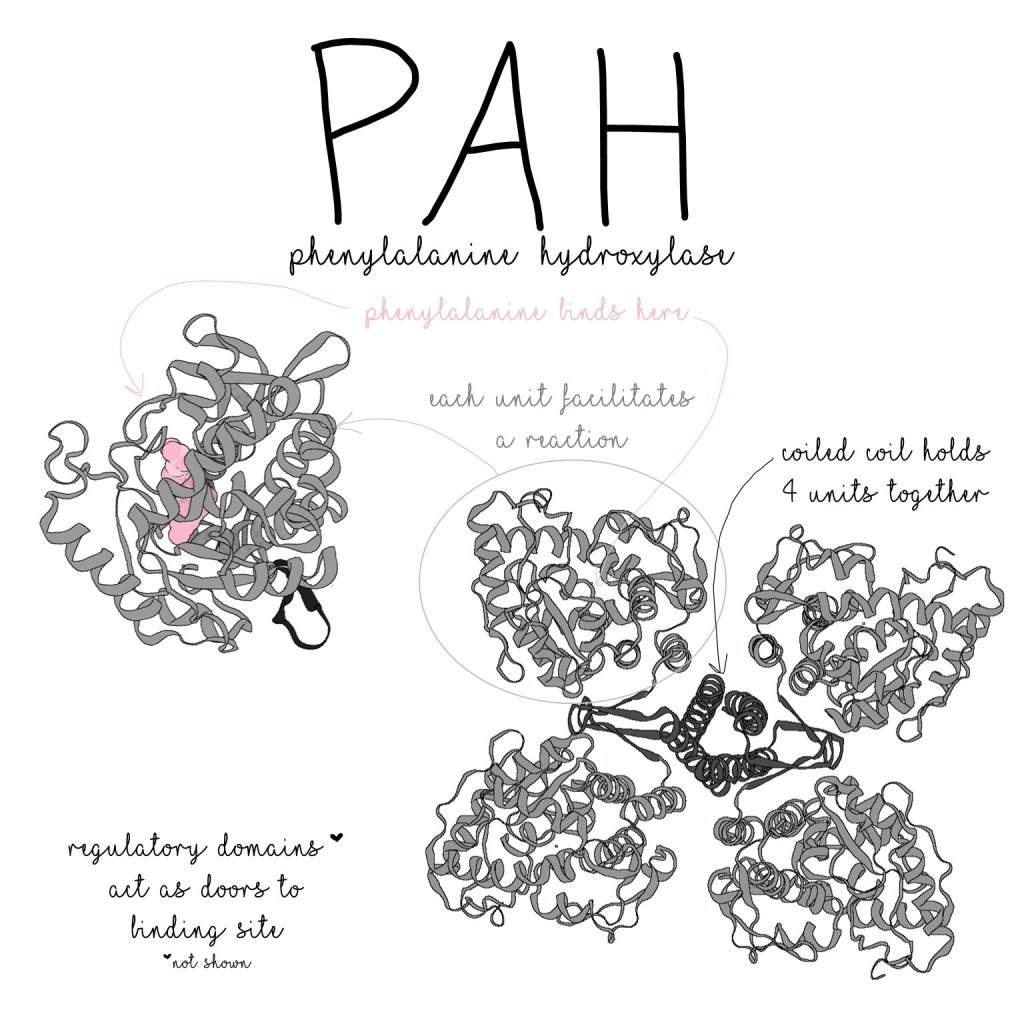

Like all molecules, the structure of PAH allows it to do its job.

PAH proteins work together in groups of four, and each PAH unit is made up of three main parts:

- The oligomerization domain (the part that sticks to the other units)

- The catalytic domain (the part that does the chemical reaction)

- The regulatory domain (the part that regulates PAH’s activity levels)

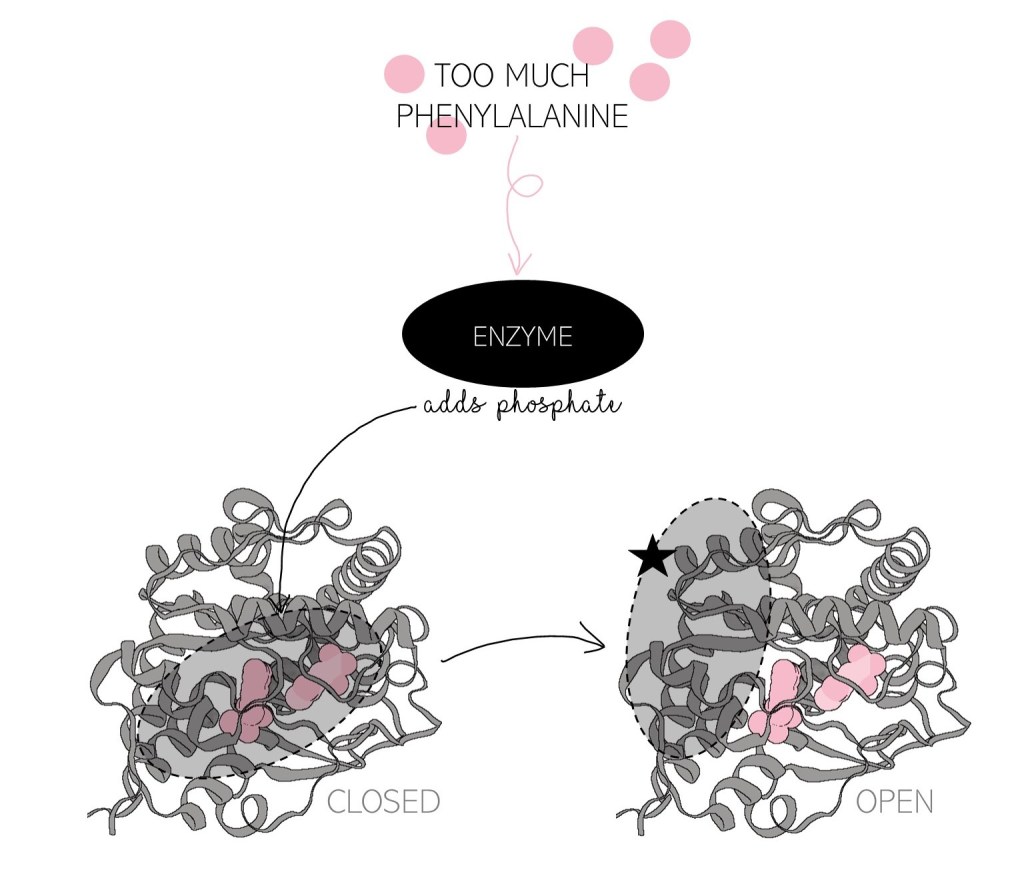

Regulation is very important since some amount of phenylalanine is needed to make proteins with–PAH can’t break down all of it! Other enzymes add and remove a phosphate molecule from PAH to signal whether or not more phenylalanine is needed. When there is too much phenylalanine around, a phosphate is added and the regulatory domain moves out of the way, like opening a door, letting phenylalanine into the catalytic domain. When there is not enough phenylalanine, removing the phosphate triggers the door to close– the regulatory domain blocks phenylalanine from accessing the catalytic domain, preventing it from being broken down.

Genetic mutations can mess with PAH’s ability to adopt the correct shape and when PAH doesn’t fold correctly, its reaction and/or its regulation is ruined. PAH loses its ability to break down phenylalanine, causing phenylketonuria, PKU, which is incredibly deadly if it isn’t detected and addressed early. Fortunately, phenylalanine-based toxins can be detected in the urine or blood (hence, the heel prick) and super specific diets limiting the consumption of phenylalanine can prevent toxins from building up to lethal levels. Even though PKU is not a super common disease, screening for PKU immediately after birth can give healthcare workers and parents the opportunity to treat it from the very beginning, before it’s too late, and save that baby’s life.

It only takes days for PKU to become fatal, demonstrating just how essential PAH is to our health!

Flydal, M.I. and Martinez, A. (2013), Phenylalanine hydroxylase: Function, structure, and regulation. IUBMB Life, 65: 341-349. https://doi.org/10.1002/iub.1150

https://www.babysfirsttest.org/newborn-screening/conditions/classic-phenylketonuria-pku

Structures: PBD 2PAH (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/2PAH) and 1MMK (https://www.rcsb.org/structure/1MMK)